On Wednesday, October 12, 2022, at 10 a.m. EDT, the Supreme Court of the United States will hear oral arguments in The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, No. 21-869. William H. Milliken, a director in Sterne Kessler’s Trial & Appellate Practice Group, will be live-tweeting updates from the firm’s account, @sternekessler. The live-tweeting will begin at 9:30 a.m. EDT and continue throughout the proceedings.

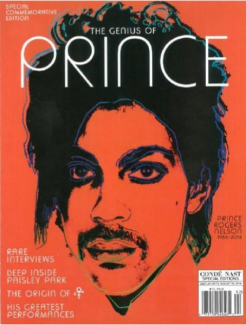

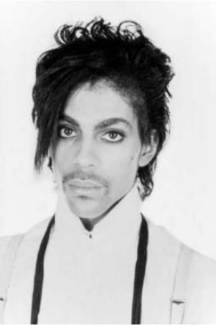

Warhol is a blockbuster copyright case involving the proper scope of the “fair use” defense to copyright infringement. The issue is whether Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series” works, including the “Orange Prince” work (below, left) licensed to the Condé Nast commemorative magazine, constitute a fair use of Lynn Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph of Prince (below, right). Orange Prince, along with eleven other works in the Prince Series, are silkscreen paintings based on the Goldsmith photograph. The Prince Series also consists of two screen prints and two drawings based on the same photograph. (There is some dispute between the parties as to whether the “use” at issue is limited to AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince or encompasses the creation and display of the Prince Series more broadly.)

The Copyright Act instructs that, in determining whether a given use qualifies as “fair,” courts must consider four factors. The first factor is “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes.” The Supreme Court has characterized this factor as an inquiry into whether the use is “transformative.”

The specific question presented in Warhol concerns the appropriate legal test for determining whether a given use qualifies as “transformative.” AWF, relying on the Supreme Court’s decision in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, contends that a use is transformative when it can “reasonably be perceived” to “add something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression meaning, or message.” Goldsmith, in contrast, argues for a much narrower definition: a use is transformative only where copying is necessary to accomplish a distinct creative end—for example, when the new use comments on or parodies the original. The United States, appearing as amicus curiae, submits that “no single test or shorthand formulation can capture all the ways in which particular uses can be fair.” The Government argues, however, that Goldsmith should prevail in this case, contending that AWF’s use was not fair because it “served the same purpose that Goldsmith’s own photographs have previously served”—namely, “a visual depiction of Prince to accompany an article about Prince in a popular print magazine.”

The Court’s decision in Warhol could have major implications in the world of copyright. Copyright law in general—and the fair use doctrine in particular—attempts to strike a balance: incentivizing and protecting the creation of original creative work, on one hand, while also facilitating the ability of artists to use others’ original work to create expression that is innovative in its own right. Make the fair-use doctrine too broad, and the former aim is frustrated; make it too narrow, and the latter aim is compromised. There is general agreement, for example, that the fair use doctrine should not protect a filmmaker who rips off a popular novel by simply adapting it to the screen, but should protect a book critic who reproduces passages of that novel as part of a book review. In between those extremes, however, is an expansive gray area. Where in that gray area the legal line is drawn matters immensely to writers, musicians, filmmakers, photographers, computer programmers, and countless other types of creators.

The firm will continue to provide updates and analysis on this closely watched case up to the Court’s decision and beyond.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates