An inventor’s own prior art cannot be used against her under Section 102(e) of the Patent Act, 35 U.S.C.A. § 102(e). But this so-called “secret” prior art might be available when the reference names more — or fewer — inventors.

The courts have said that it is “axiomatic” that A’s patent is not prior art to A & B’s patent even though A is “another.” But the real story is far more complicated.

Section 102(e) creates a category of secret prior art, but it cannot be used against its own inventor

Section 102(e), a pre-AIA (America Invents Act) statute, applies to most U.S. patents claiming priority before 2013. For that reason, courts, the patent office and lawyers will deal with Section 102(e) for nearly 20 more years.1 So, Section 102(e) fights remain likely for many years.

A patent application remains secret before it is published 18 months after it’s filed according to Section 122(b)(1)(A) of the Patent Act, 35 U.S.C.A. § 122(b)(1)(A). But the prior art date is the application filing date — not the publication date — once it is published.2

Similarly, issued patents become prior art under Section 102(e) as of their filing date. But there is a saving provision in Section 102(e): the secret prior art can only be used against “another.”3 And this language makes Section 102(e) a real puzzle.

The relevant portion of the statute is reproduced here:

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless… —(e) the invention was described in — (1) an application for patent, published under section 122(b) [the pre-grant publication statute], by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent or (2) a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent.4

The statute is complicated because of the way the phrase “by another” has been interpreted by the United States Patent & Trademark Office and the courts. On its face, “by another” could reasonably and simply be interpreted to mean by “a separate inventive entity.” But it is not that simple.

‘Another’ is any change from the original named inventors — but a leading case is ambiguous

Early Federal Circuit case law suggests that a reference without exactly the same inventors still might not qualify as Section 102(e) prior art, despite technically being to “another.”

In In re Kaplan,5 for example, the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences rejected an application, filed by Kaplan and Walker, for double patenting over a commonly owned patent to Kaplan.

The Federal Circuit reversed. The inventive process of Kaplan and Walker was, “generally speaking,” an improvement over the Kaplan process.6 The court noted that the “sole inventor and joint inventors are separate ‘legal entities.’”7

This suggests the earlier patent or published application is “by another” unless there is one-to-one correspondence among the named inventors.

But the Federal Circuit then quoted as “axiomatic” this section of In re Land:

When the joint and sole inventions are related, as they are here, inventor A commonly discloses the invention of A & B in the course of describing his sole invention and when he so describes the invention of A & B he is not disclosing “prior art” to the A & B invention, even if he has legal status as “another.”8

This quoted portion from In re Land suggests the earlier patent or published application may not be prior art, even though it lacks one-to-one overlap in the named inventors.

The Federal Circuit in In re Kaplan then proceeded to reverse the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI) on several grounds.

With respect to Section 102(e), the court reversed because the rejection “used the disclosure of the appellants’ joint invention in the Kaplan patent specification as though it were prior art, which it is not, to support the obviousness aspect of the rejection.”9

The Federal Circuit thus held that using a prior invention against a later joint invention “amounts to using an applicant’s invention disclosure, which is not a 1-year time bar, as prior art against” the inventor.10

The dicta from In re Kaplan, on first reading, certainly suggests that overlapping inventors are broadly protected from Section 102(e).

But an analysis of the underlying case, In re Land,11 clarifies that this is not the case. In In re Land, Land and Rogers applied for a patent and the Examiner rejected all claims.

The BPAI affirmed the rejections based, in part, on a patent to Rogers alone.12 The Rogers patent was prior art only under Section 102(e) because it was filed before but issued after the Rogers and Land application.13

The examiner assumed that a reference to Rogers alone was available as prior art under Section 102(e).14 In discussing the case, the court first noted that its prior case law held that “one of the joint applicants” was “not ‘another’ within the meaning of section 102(e)” to both joint inventors.15

The court clarified that any change in inventors made the patent to another.

It also stated, however, that the “real issue is whether all the evidence, including the references, truly shows knowledge by another prior to the time appellants made their invention or whether it shows the contrary.”16

The court in In re Land thus appears to have established the rule as identified in In re Kaplan. But, significantly, the holding of In re Land continues. There was, in In re Land, “no indication that the portions of the references relied on disclose anything they did jointly.”17

In re Land thus requires a fact investigation:

When the 102(e) reference patentee got knowledge of the applicant’s invention from him, as by being associated with him, or, as here, had knowledge of the joint applicants’ invention by being one of them, and thereafter describes it, he necessarily files the application after the applicant’s invention date and the patent as a “reference” does not evidence that the invention, when made, was already known to others. Evidence of such a state of facts, whatever its form, must be considered.18

Although Kaplan does not discuss the fact-specific inquiry, the court in In re Land mandates it.

Modern cases have reaffirmed In re Land and have thus performed a fact inquiry, further suggesting that Kaplan‘s language is imprecise

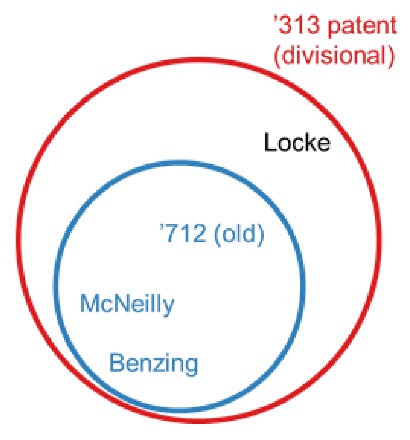

Since Kaplan, the Federal Circuit has looked to the scope of disclosure in applying Section 102(e) with overlapping inventors. For example, in Applied Materials Inc. v. Gemini Research Corp.,19 Applied sued Gemini for patent infringement in the Northern District of California on the ‘313 patent.

The district court granted summary judgment to Gemini invalidating the asserted patents. The district court found that an earlier patent, the ‘712 patent, was Section 102(e) art to a later divisional patent, the ‘313 patent.20

The ‘712 patent named McNeilly and Benzing as inventors.21 The later ‘313 patent named McNeilly, Benzig, and Locke as inventors. So on its face, the ‘712 patent was “by another” and should qualify as 102(e) prior art to the ‘313 patent.

In reversing the Section 102(e) ground, the Federal Circuit held that “if the invention claimed in the ‘313 patent is fully disclosed in the ‘712, this invention had to be invented before the filing date of the ‘313 patent and the ‘712 patent cannot be 102(e) prior art to the ‘313 patent.”22

The Federal Circuit also reversed on an unrelated collateral estoppel ground.23

One district court characterized the holding of Applied Materials very narrowly, finding that Applied Materials removes parent patents from the universe of Section 102(e) prior art where the “parent patent fully discloses an invention that in fact is the work of an overlapping inventive entity and that is claimed in a continuing application listing that entity.”24

In that event, the district court found, “the presence of that subject matter in the earlier patent indicates that the present invention was already in existence as of the filing date of the parent application.”25

The key question thus seems to be whether the inventor or inventors of the later patent were those who invented the portions of the earlier patent asserted to be prior art.

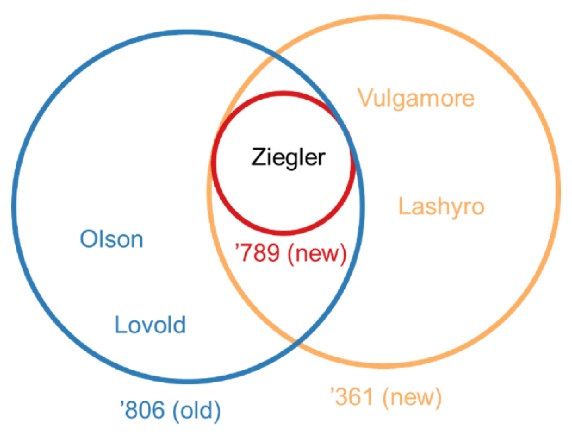

For example, in Riverwood International Corp. v. R.A. Jones & Co.,26 Riverwood sued Jones for infringing two patents. The Northern District of Georgia found the patents to be infringed but invalid.

The invalidity finding was based on the conclusion that, under Section 102(e), the earlier ‘806 patent was prior art to the later ‘789 and ‘361 patents.27 The Federal Circuit vacated and remanded. The ‘806 named Ziegler, Olson, and Lovold.

The ‘789 named Ziegler alone, while the ‘361 named Ziegler, Lashyro, and Vulgamore. At trial, Riverwood argued that the ‘806 was not prior art because Ziegler was the sole inventor of the portions of the ‘806 patent that served as the basis for the ‘789 and ‘361 patents.

The trial court found that this was an admission that the ‘806 patent was prior art to the other patents. The Federal Circuit ultimately held that ‘806 was not prior art only if Ziegler was the sole inventor of the portions of the ‘806 patent offered as prior art.

The upshot is that the Federal Circuit, in cases like Applied Materials and Riverwood, has confirmed that evaluating whether a reference is available under Section 102(e) can be a fact intensive inquiry where there are overlapping inventors.

So inventorship arguments about Section 102(e) art are available but should be made based on factual analysis and not on a categorical logical argument.

A PTAB case demonstrates the importance of a rigorous fact-based inquiry where the status of Section 102(e) prior art is challenged

A Patent Trial & Appeal Board (PTAB) case explains why simple scope-of-disclosure arguments may not be adequate to escape Section 102(e).

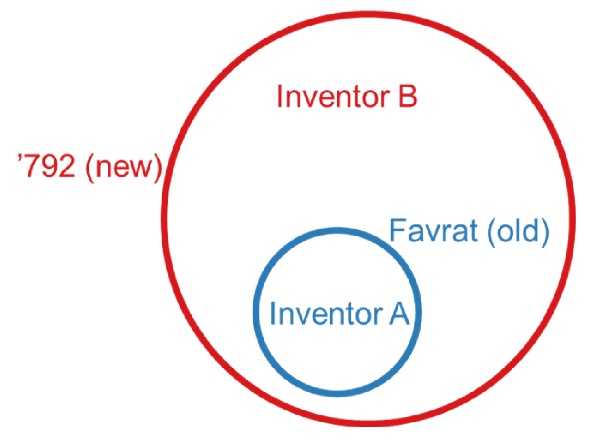

In MaxLinear, Inc. v. Cresta Tech. Corp.,28 MaxLinear filed an IPR alleging claims of the ‘792 patent were invalid over the Favrat reference.

The only disputed issue was whether Favrat was prior art to the ‘792 patent under Section 102(e). The Favrat reference was invented by Favrat, Margairaz, Porret, and Python. MaxLinear refers to those inventors as Group A.

The ‘792 patent was invented by the Group A inventors (Favrat, Margairaz, Porret, and Python) plus another group of inventors (the so-called Group B inventors: Mombers, Perring, Duc, and Carnero). The ‘792 patent was filed two years after Favrat and did not share any priority claim.

The Board found that earlier testimony in the ITC showed that one of the Group B inventors “conceived of at least one” of the claim limitations at issue. The patent owner in MaxLinear had two arguments that the Favrat reference couldn’t be Section 102(e) art.

First, the patent owner offered a logical argument that the overlapping scope of disclosure meant that the Favrat reference was not available as Section 102(e) prior art.

The patent owner argued that the inventorship of the ‘792 patent was coextensive with the Favrat reference, as the Favrat reference disclosed the full subject matter of the ‘792 claims.

The Board found this was of no moment because it was possible that the group B inventors could have “contributed to subject matter that was disclosed but not claimed in [the Favrat reference]” and would therefore not have been eligible to be co-inventors.

Second, the patent owner relied on the explicit holding of In re Kaplan. Specifically, the patent owner argued that under In re Kaplan, prior art invented by Group A cannot be Section 102(e) art to a joint invention by Groups A and B.

In preparing its analysis, the Board found, without citation, that “if at least one member of Group B conceived of at least one limitation of claim 1, then Favrat is ‘by another’ as required by § 102(e).”

This is consistent with In re Kaplan 789 F.2d at 1576. But the Board found that the key distinguishing feature was language from In re Kaplan that the bar on Section 102(e) only applied where “the joint and sole inventions are related, as they are here.”

Because the ‘792 patent did not claim priority to Favrat, the PTAB concluded that the Favrat reference was Section 102(e) art to the ‘792 patent.

The PTAB thus attempted to create a bright-line rule from In re Kaplan. But is such a bright-line rule warranted? Are there a set of facts in MaxLinear that, if proven, would remove Favrat as Section 102(e) prior art under an In re Land-type inquiry?

There probably are, and parties seeking to remove a reference from the universe of Section 102(e) prior art may have to undertake a fairly deep and fact-intensive inquiry to get there.

It is also important to note that the MaxLinear result might have been different at the district court because in district court (subject to the presumption of validity under 35 U.S.C.A. § 282) a challenger must “introduce clear and convincing evidence on all issues relating to the status of a particular reference as prior art.”29

This does not apply to the PTAB where the standard of proof is lower for a Petitioner, who has to prove unpatentability only by a “preponderance of the evidence.”30

It’s important to note that the PTAB’s decision was never appealed, so the Federal Circuit has not had a chance to weigh in on the issues presented by MaxLinear.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that great care needs to be taken in addressing Section 102(e). Patent challengers asserting that a reference is Section 102(e) prior art should think carefully about the risk that subsequent discovery will reveal that the reference can’t be used.

And patent defenders facing a reference with some common inventors under Section 102(e) should try to develop evidence that the new and old inventors both created the relevant subject matter.

Notes

1 See 35 U.S.C.A. §§ 154 (specifying a 20-year patent term) and 286 (permitting suits for six years after patent expiration).

2 See Baxter Int‘l Inc. v. COBE Labs. Inc., 88 F.3d 1054, 1062 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (Newman, J. dissenting).

3 Id.

4 35 U.S.C.A. § 102(e) (2002) (emphasis added).

5 789 F.2d 1574, 1574 (Fed. Cir. 1986).

6 Id. at 1575.

7 Id. citing In re Land, 368 F.2d 866, 879 (C.C.P.A. 1966) (holding that an invention is prior art for obviousness under this analysis; see also South Corp. v. U.S., 690 F.2d 1368, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 1982) (adopting C.C.P.A. precedent for the Federal Circuit).

8 In re Kaplan, 789 F.2d at 1576 (alterations in original).

9 Id. at 1577 (emphasis added).

10 Id. at 1580.

11 368 F.2d 866, 868–69 (C.C.P.A. 1966) (Rich, J.).

12 Id. at 868.

13 Id.

14 Id. at 875–76.

15 Id. at 876.

16 Id. (emphasis added).

17 Id. at 881.

18 Id. at 879.

19 835 F.2d 279, 279–80 (Fed. Cir. 1987).

20 Id. at 280.

21 Id. at 281.

22 Id.

23 Id.

24 Purdue Pharma L.P. v. Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, 98 F. Supp. 2d 362, 381 (S.D.N.Y. 2000).

25 Id.

26 324 F.3d 1346, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

27 Id.

28 No. IPR2015-00594, (P.T.A.B. Aug. 15, 2016).

29 See Sandt Tech. Ltd. v. Resco Metal & Plastics Corp., 264 F.3d 1344, 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

30 See Celgene Corp. v. Peter, 931 F.3d 1342, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates