2024 was another busy year for district court decisions! There were multiple jury trials, case-dispositive design patent decisions, and claim construction decisions across a range of venues and at a range of case postures. We summarize below four noteworthy decisions. Homy Casa Limited v. Jili Creation Technology Co., Ltd. and Fiskars Finland Oy AB v. Woodland Tools Inc. deal with infringement questions at the complaint (Homy Casa) and summary judgment (Fiskars) stages. PainTEQ, LLC v. Omnia Medical, LLC presents an interesting priority date assessment and indefiniteness analysis at the summary judgment stage, and Todd Deetsch v. Peter Lei et al. considers the scope of the claim in view of functionality at the claim construction stage.

Several of the cases discussed below involve questions that have never been asked before or answers that have never been given before in design patent cases. Predicting what will happen on appeal can be difficult, but we would not be surprised if at least aspects of the decisions discussed below are reversed or remanded on appeal. These will certainly be cases to watch to see what happens as they progress, including whether the Federal Circuit affirms, reverses, or remands.

Homy Casa Limited v. Jili Creation Technology Co., Ltd.

Homy Casa Limited filed a district court action in the Western District of Pennsylvania alleging that Jili’s “Tapscott Solid Back Side Chair” infringes four of its design patents: U.S. Patent Nos. D808,669S, D920,703S, D936,991S, and D936,992S. Both Homy Casa and Jili sell chairs online, and the four asserted patents relate to chair designs. Jili moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim.

The court stated that the operative question is whether Homy Casa has plausibly alleged that an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art, would consider the chairs substantially the same such that the observer might purchase the Tapscott Solid Back Side Chair when they me ant to purchase the claimed chair. In the context of a motion to dismiss, courts generally consider only the allegations contained in the complaint, exhibits attached to the complaint, and matters of public record. Here, the court took judicial notice of a number of other patents (all of which were listed as a “cited reference” in the asserted patents) to provide the prior-art context for the infringement analysis.

The court held that Homy Casa had not satisfied its burden and granted the motion to dismiss. The court’s rationale for all four asserted patents is very similar. U.S. Patent No. D808,669S can, therefore, be used as an exemplary analysis. The court found that there are a number of differences between the claimed design and the accused product. For example, the patent shows a chair with an interior section or cushion that is separate from the rest of the seat, but the accused product has no such internal section. Additionally, the patent shows a chair with a flat seat, but the accused product has a curved seat. And the patent shows a chair with a back that is nearly vertical from the seat to halfway up, and then extends off at an angle; but the back of the accused product extends at an angle from the seat in nearly a straight line. The below images show the patented design (on the left) and the accused product (on the right).

product from the patented design.

Fiskars Finland Oy AB v. Woodland Tools Inc.

Fiskars Finland Oy AB filed a district court action in the Western District of Wisconsin alleging a variety of claims, including infringement of two design patents: U.S. Patent Nos. D720,969 (D’969) and D684,828 (D’828). Fiskars and Woodland compete in the hand-held gardening tool market. The D’969 patent claims an ornamental design for gardening snips, and the D’828 patent claims an ornamental design for a trimming tool commonly referred to as a “lopper.” Wood-land moved for a variety of relief, including excluding Fiskars’ infringement expert from testifying at trial if the case proceeds to trial and summary judgment of noninfringement.

Regarding Woodland’s motion to exclude Fiskars’ infringement expert, the court granted the motion, explaining that Fiskar’s expert’s infringement analysis is fatally flawed, including because he limited his consideration of the prior art to a single piece and he did not consider the functional aspects of the claimed design and accused products.

Regarding infringement of the D’969 patent, the court agreed with Woodland that because the design includes functional features, it is appropriate to exclude those features from the claimed design. In particular, the court agreed that the functional features include a pair of handles configured to be gripped by the hand, connected with a pivot mechanism at the end, so that the handles may operate the blades at the other end and some form of stop at the end of the handles. Additionally, because the tool is to be gripped by the hand, the court agreed that it is functional to avoid sharp edges in the grip area. Thus, the court said the ornamental components of the design are the shape of the handles and the pivot mechanism.

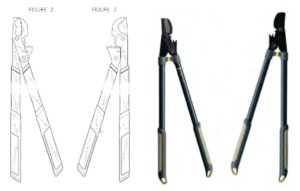

Having construed the claimed design the court then proceeded to compare the claimed design to the accused product. The below images show a side-by-side comparison of figures from the patent (on the left) and photographs of the accused product (on the right).

The court then turned to construing the D’828 patent claim. Regarding functionality, the court rejected Fiskars’ argument that the claimed gears, linkages, and handle shape are not dictated by function because there are loppers without gears, linkages, or dogleg-shaped handles.

The court said this was a simplistic view of functionality, stating that just because no single option is strictly required does not mean that the choice to use one of the options creates a nonfunctional, ornamental element. The court found that the use of gears and the size and shape of the gears are driven primarily by functional considerations and should be excluded from the claim scope. Additionally, the court stated its belief that Fiskars’ utility patent on a geared lopper reinforces that these are functional aspects. Thus the court construed the patent to claim an ornamental design of the cutting tool shown, excluding the functional elements of the basic layout of the tool (two longer handles configured to be drawn together by hand, connected at a pivot so as to bring two shorter blades together) and the gear-driven cutting apparatus.

With that construction, the court then turned to the side-by-side comparison of the claimed design (on the left below) and the accused lopper (on the right below).

For this patent, too, the

PainTEQ, LLC v. Omnia Medical, LLC

PainTEQ filed suit in the Middle District of Florida. In response, Omnia filed counterclaims, asserting, among other things, that PainTEQ’s LinQ surgical cannula infringed two of its design patents: U.S. Patent Nos. D905,232 (D’232) and D922,568 (D’568). PainTEQ and Omnia are both involved in the surgical device business. Although they once had a business relationship, that relationship fell apart and resulted in the instant case. PainTEQ moved for summary judgment of a variety of issues, including noninfringement of Omnia’s two asserted design patents and invalidity of the D’568 patent due to indefiniteness.

The big dispute for infringement was around whether the asserted claims could claim priority to an earlier filing date (and, therefore, what was properly included within the scope of the prior art). On their face, both asserted patents claimed priority to an earlier utility patent. But that utility patent did not include the figures in the design patents. Omnia argued that although the exact figures in the design patents were not in the utility patent, several figures in the utility patent and the written description in the specification have sufficient similarity to the design patents to support the priority claim. The district court agreed, stating that a design patent may claim priority to an earlier utility patent even if the utility patent does not contain an exact replica for the design later claimed in the design patent. The court said, here, the earlier utility patent had enough similarities to the later design patents that the priority claim was proper. In particular, the court said the written description in the utility patent properly describes the later claimed designs, explaining that “‘a person of ordinary skill’ could conclude that the D’232 and D’568 Patents derive from the written description in the [earlier utility] Patent.”

With the scope of prior art defined, the court applied it to its infringement analysis and granted summary judgment of non-infringement of the D’568 patent but not the D’232 patent. The below images show figures from the asserted patents on the left and the accused PainTEQ product on the right. The court came to this different conclusion based on the narrower scope of protection of the D’568 patent (which the court ruled covered only the dimensions of the barrel of the cannula). Because the dimensions of the barrel are not exact between the D’568 patent and the accused PainTEQ product, the court ruled that no reasonable juror could conclude that the designs are “substantially similar.”

Todd Deetsch v. Peter Lei et al.

Todd Deetsch filed a case in the District Court for the Southern District of California alleging that Peter Lei, Lumia Products Co. LLC, Amazon.com, Inc., and Amazon.com Services LLC infringe U.S. Design Patent Nos. D595,529 (D’529) and D595,530 (D’530). Mr. Deetsch designs and sells continuous positive airway pressure (“CPAP”) pillow products, which he asserts are covered by his patents. The parties filed claim construction briefing, requesting that the court construe the two asserted design patents.

The main dispute was what functional aspects, if any, should be excluded from the scope of protection. The patentee argued none, and the defendants argued a long list. The court acknowledged that “in deciding whether to attempt a verbal description of the claimed design, [a district] court should recognize the risks entailed in such a description, such as the risk of placing undue emphasis on particular features of the design and the risk that a finder of fact will focus on each individual described feature in the verbal description rather than on the design as a whole.” However, here, the court found that some description was appropriate because “[w]here a design contains both functional and non-functional elements, the scope of the claim must be construed in order to identify the non-functional aspects of the design as shown in the patent.” The court said that in determining whether certain features of the claimed design are purely functional, a court may consider whether the advertising touts particular features of the design as having specific utility.

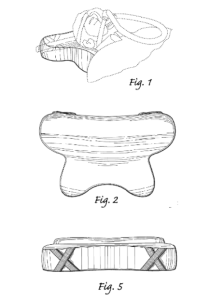

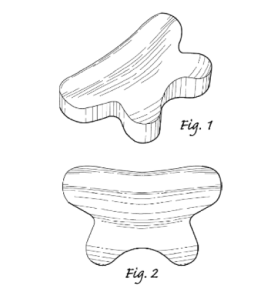

Turning first to the D’529 patent, it is entitled “Pillow Insert” and claims “The ornamental design for a pillow insert, as shown and described.” Figures 1 and 2 from the patent are reproduced below.

Turning next to the D’530 patent, it is entitled “Pillow With X Straps” and claims “The ornamental design for a pillow with X straps, as shown and described.” Figures 1, 2 and 5 of the patent are reproduced below.

Like with the D’529 patent, the court considered Defendants’ evidence of how the patentee advertises its products and held that the pillow’s butterfly shape, orthopedic curve, and X straps are functional and, therefore, not part of the claimed design.

This article appeared in the 2024 Design Patents Year in Review: Analysis & Trends report.

Related Services

Related Events

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates