In 1884, the Supreme Court upended the view that reproductions made by a machine could not qualify for copyright protection. The Court held that a “machine-made” image, meaning a photograph, titled Oscar Wilde, No. 18. constitutes a work of authorship eligible for copyright protection because it was the result of the photographer’s original artistic choices (e.g., posing the photographed subject, Oscar Wilde, in front of the camera; selecting and arranging the environment pictured in the photograph; selecting the lighting in the photograph).1

Since then, the bounds of what constitutes a work of “authorship” eligible for copyright protection have been tested. The prevailing view is that works resulting from non-human entities such as nature and animals may not qualify. For example, the Ninth Circuit has held that a book containing words “authored by non-human spiritual beings” can only gain copyright protection if there is “human selection and arrangement of the revelations.”2 The same court held that a monkey cannot register a copyright in photos it captures with a camera because the authorship-related terms used within the Copyright Act exclude animals.3 The Seventh Circuit rejected a copyright claim in a “living garden” because “[a]uthorship is an entirely human endeavor” and “a garden owes most of its form and appearance to natural forces.”4

Those bounds continue to be tested, the most recent challenge being Steven Thaler’s attempt to register a two-dimensional artwork that was created solely by a machine with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Thaler’s Challenge

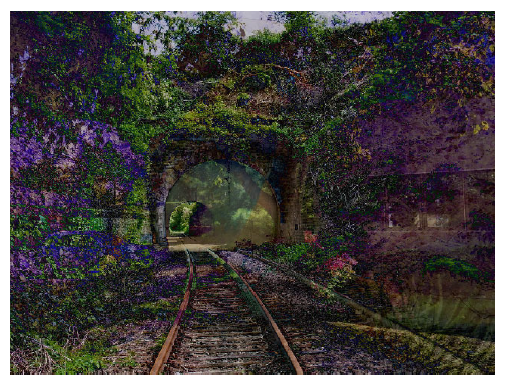

Thaler, creator and owner of the “Creativity Machine,” filed an application with the U.S. Copyright Office (“Office”) to register a two-dimensional artwork titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise,” pictured below.

The work depicts a colorful rendering of an idyllic setting featuring a train track surrounded by overgrown foliage and wisteria trees, and clearly exhibits the necessary modicum of creativity to satisfy the first prong of Copyright Law’s originality requirement. As for the work’s genesis, the copyright application stated that the work was “autonomously” created by a computer algorithm running on the machine, and accordingly listed “Creativity Machine” as the author of the artwork, and Thaler as the owner of the artwork by virtue of his “ownership of the machine.” The Office refused to register the claim on the basis that it did not satisfy the second prong of Copyright Law’s originality requirement, which considers “authorship.” According to the Office, the claim lacked the “human authorship” necessary to support a copyright claim.5

Thaler requested that the Office reconsider its refusal because, he argued, the human authorship requirement is unconstitutional and unsupported by statute and case law.6 Upon reevaluation, the Office stated that it would not “abandon its longstanding interpretation of the Copyright Act, Supreme Court, and lower court judicial precedent that a work meets the legal and formal requirements of copyright protection only if it is created by a human author.”7 Thaler made a second request for reconsideration, renewing the same arguments and stating that the Office “should” register copyrights in machine-generated works because doing so would “further the underlying goals of copyright law, including the constitutional rationale for copyright protection.”8 Furthermore, Thaler argued that the work-for-hire doctrine of copyright law does not preclude non-human entities from being authors. Under that doctrine, the author is not the party that actually created a work, but the party that employed or contracted the party that actually created the work, provided that the parties agree in writing that the work is a work made for hire.

The Copyright Review Board affirmed the Office’s refusal to register a work created solely by a non-human entity. In its opinion, the Board cited the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices manual and stated that “copyright law only protects ‘the fruits of intellectual labor’ that ‘are founded in the creative powers of the [human] mind.’” Yet no Compendium section explicitly addresses artificial intelligence.9 The Board decided that Thaler failed to (1) provide evidence that the AI’s artwork was the product of human authorship or (2) convince the Office to depart from its jurisprudence.10 The Board also determined that Thaler could not be the author of the work based on the work-for-hire doctrine. According to the Board, the “Creativity Machine” cannot enter into binding legal contracts and thus, cannot meet this requirement. In analyzing the language of the statute, the Board also found that “the work-for-hire doctrine only speaks to the identity of a work’s owner, not whether a work is protected by copyright.”11 The Board therefore concluded that “…human authorship is a prerequisite to copyright protection in the United States and that the Work therefore cannot be registered.”

Takeaways

Although the Board’s decision makes it clear that works made solely by autonomous machines are not currently eligible for registration with the U.S. Copyright Office, it left open the possibility that they might one day be: “[I]t is generally for Congress…to decide how best to pursue the Copyright Clause’s objectives…[the Board] cannot second-guess whether a different statutory scheme would better promote the progress of science and useful arts.”12 Until then, or until a U.S. court decides in favor of granting copyright protection to AI-generated works (which seems unlikely given the Eastern District of Virginia’s recent ruling that an AI machine cannot qualify as an “inventor” under the U.S. Patent Act13), it seems that a work created with the assistance of AI may be eligible for copyright protection in the U.S. only if it is the result of significant amount of input from a human. Alternatively, if a work is the sole result of AI, it may qualify for trademark protection if used as a source identifier because human authorship is not a prerequisite to trademark protection.

[1] Burrows-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 61 (1884).

[2] Urantia Found. v. Kristen Maaherra, 114 F.3d 955, 957–59 (9th Cir. 1997) (holding that “some element of human creativity must have occurred in order for the Book to be copyrightable” because “it is not creations of divine beings that the copyright laws were intended to protect”).

[3] Naruto v. Slater, 888 F.3d 418, 426 (9th Cir. 2018).

[4] Kelley v. Chicago Park Dist., 635 F.3d 290, 304 (7th Cir. 2011).

[5] Initial Letter Refusing Registration from U.S. Copyright Office to Ryan Abbott (Aug. 12, 2019).

[6] Letter from Ryan Abbott to U.S. Copyright Office at 1 (Sept. 23, 2019) (“First Request”).

[7] Id. at 1-2.

[8] Letter from Ryan Abbott to U.S. Copyright Office at 2 (May 27, 2020) (“Second Request”).

[9] U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, COMPENDIUM OF U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE PRACTICES § 202.02(b) (2d ed. 1984)

[10] Review Board (Feb. 14, 2022) at 2-3.

[11] This issue is distinct from whether a computer program authored by a human can be copyrighted. Computer programs and code can be copyrightable when authored by a human, although courts look at originality and various aspects of the program such as the structure, sequence, and organization. See The Computer Software Act of 1980 (that amended § 101 of the 1976 Act); Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp., 714 F.2d 1240 (3d Cir. 1983), cert. dismissed, 464 U.S. 1033 (1984).

[12] Id., citing Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 212 (2003).

[13] Thaler v. Hirshfeld, No. 120CV903LMBTCB, 2021 WL 3934803 (E.D. Va. Sept. 2, 2021).

This article appeared in the March 2022 issue of MarkIt to Market®. To view our past issues, as well as other firm newsletters, please click here.

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates