Law360 (March 4, 2020, 6:13 PM EST) — There are currently seven coronaviruses known to infect people. Four of them are typical cold viruses and only rarely result in death. The current Wuhan coronavirus, COVID-19[1] can be lethal and is the third major global outbreak of a coronavirus in the past 20 years, joining its close cousins Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome[2] and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome.[3] There is currently no vaccine against the Wuhan coronavirus.

Addressing this current global coronavirus outbreak has focused extreme attention on the role patent systems play in encouraging investment in vaccines and cures for this illness. The private sector requires exclusive rights to undertake the massive investment needed to develop vaccines and treatments.

Government could play a much more significant role in dealing with these pandemics, not only in terms of treatment, but more importantly, with proactive measures such as vaccine development and medical diagnostics.

The patent systems around the world are being tested by implication as the scramble to address this widening pandemic unfolds. It is important to understand the science behind this viral outbreak to fully appreciate the tension among patent rights, investments, governments and public health.

COVID-19

This is what what the virus looks like:[4]

It is believed that COVID-19 emerged from a market in Wuhan selling wild animals alongside seafood. The coronavirus is believed to spread primarily via respiratory droplets produced when an infected person talks, coughs or sneezes (similar to how influenza and other respiratory pathogens spread).

People nearby can be infected through the inhalation of these droplets through their eyes, mouth, or nose, or perhaps by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their own mouth, nose or eyes. Based on previous studies, some human coronaviruses can remain infective on materials such as metal, glass or plastic for up to nine days.[5]

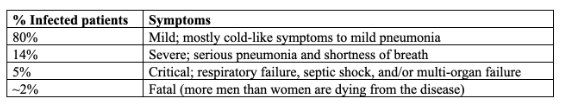

COVID-19[6] symptoms can vary widely among infected people:

The fatalities are likely an overestimate of the mortality rate, given that many mild cases might go undiagnosed. In the SARS outbreak of 2003, about 10% of infected people died, while the 2012 outbreak of MERS killed 23% of infected people.[7]

Those most likely to develop severe or critical disease are the elderly and people with preexisting illnesses.[8] In fact, patients over the age of 80 have the highest risk, with about 15% of them dying. Interestingly, children nine years of age or younger do not appear at risk, and relatively few cases are seen among children.[9]

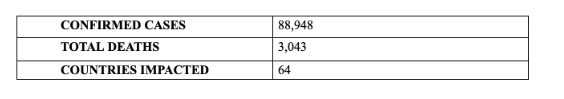

The global spread[10] of the Wuhan Coronavirus is extensive:

Currently, less than 5% of all children[11] are routinely fully immunized with the vaccines recommended by the World Health Organization: Diphtheria, Hepatitis A and B, Haemophilus influenzae type b, Human papillomavirus, Influenza, Measles, Mumps, Pertussis, Rubella, Pneumococcal disease, Poliomyelitis (Polio), Rotavirus, Tetanus and Varicella.

Even with this low percentage of fully immunized children, global sales of vaccines totaled $54 billion in 2019 and are predicted to near $60 billion in 2020.[12] The federal government currently pays for about 95% of all publicly funded childhood vaccines distributed in the U.S., primarily for children who are uninsured or Medicaid-eligible.[13]

Vaccine Development — Cost and Process

Vaccines[14] are complex biological compositions that confer immunity against specific diseases, typically by provoking an immune response in the body. An immune response can be provoked by using an attenuated or dead form of the pathogen, parts of microbes, microbial deoxyribonucleic acid or compounds that mimic microbial products.

The use of such compounds induces the production of specific immune cells that remain in the body for long periods of time. Because of such long-term immune memory, a rapid immune response typically results upon subsequent exposure to the pathogen.

The advent of vaccination started in 1796 when English physician Edward Jenner immunized a child against smallpox by injecting him with pus from a woman who had been exposed to cowpox, a close relative of smallpox. (In fact, the word vaccine comes from the Latin name for cowpox, vaccinia.) The French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur,[15] first exposed people to dead or attenuated microorganisms in the late 1800s.

And, in the 1900s, the first vaccine techniques were developed known as “glycoconjugation,”[16] in which the sugary outer coat of bacteria was linked to proteins. Between 1890 and 1950, bacterial vaccine development proliferated, followed by viral tissue culture methods from 1950-1985, leading to the Salk (inactivated) polio vaccine and the Sabin (live attenuated oral) polio vaccine.[17]

Developing a vaccine[18] typically takes years and involves a lengthy process of testing on animals, clinical trials on humans and regulatory approvals. Companies wishing to bring a new vaccine to market must invest in appropriate manufacturing facilities that are expensive and take time to construct and validate. As an example, Sanofi Pasteur Inc.’s production facility for its dengue vaccine cost more than 300 million euros (and this does not include the billion euros they spent on R&D).[19]

The significant financial investment required for vaccine development is challenging for startups and hinders overall innovation. Compared to small-molecule drugs, vaccines have smaller markets and are more complex and expensive to manufacture and test in human clinical trials. Without gaining exclusive marketing rights for some period, profit-minded companies will have no incentive to undertake the necessary research.

Intellectual Property for Vaccines

Vaccine IP is complex and characterized by multiple levels of patents, including patents directed to DNA and amino acid sequences, vectors, attenuated strains, formulations, culturing and manufacturing methods, methods of use, kits and devices for vaccine administration.

Because vaccines are often constructed using live attenuated viruses or components that have markedly different characteristics from what exists in nature, they typically qualify as patent-eligible subject matter. Trade secrets are particularly relevant to know-how related to the manufacturing process, which are complicated and difficult to design.

The ability of third parties to invent around is particularly relevant to vaccines, which often consist of multiple technologies, only some of which are patented. During the last 20 years, some 10,000 patent applications for vaccines have been submitted, mainly by national institutes of health and universities.[20] The patents mainly concern vaccines against tuberculosis, malaria and HIV. The bulk of the funding comes from the public sector because there is no market force driving this. Patent thickets are becoming an issue for vaccines, as are patent nonpracticing entities.

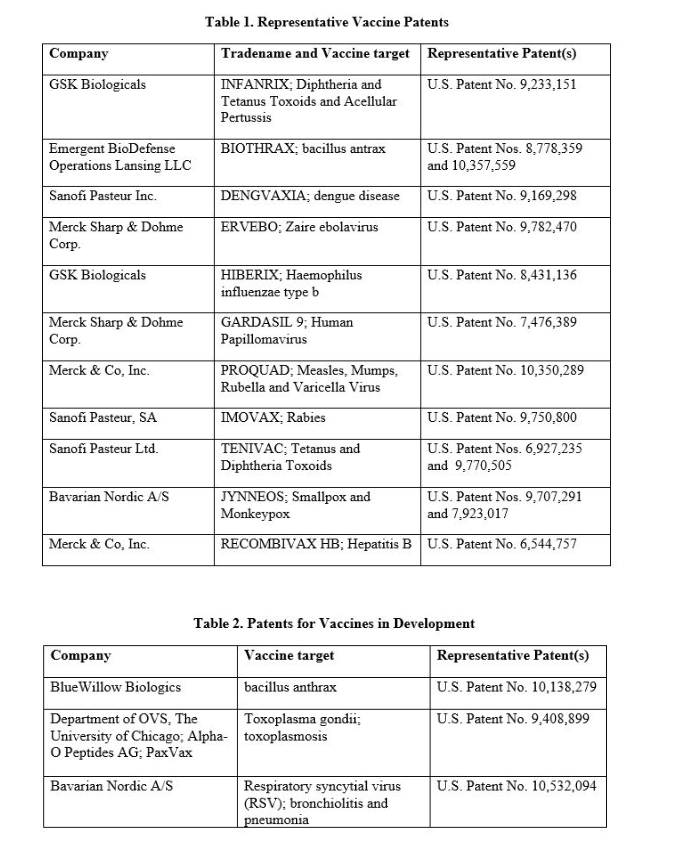

Even though innovation and drug approvals are sorely needed in this space, due to the financial investment required, fewer companies are developing vaccines. Some of the main players in the vaccine field include Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline PLC, Merck & Co. Inc. and Emergent BioSolutions Inc. Some examples of the vaccines developed, or being developed, by companies, and approved and licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are shown in the tables below.

Development of a COVID-19 Vaccine

As far as a coronavirus vaccine is concerned, various companies and others, including GeoVax Inc. and BravoVax Co. Ltd., iBio Inc. and CC-Pharming, Takis Biotech and EvviVax, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations[21] and GSK, University of Queensland, CureVac AG, Moderna Inc., Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Inovio Pharmaceuticals Inc. have risen to the challenge, unveiling in recent weeks plans to develop a coronavirus vaccine.

China is testing Gilead Sciences Inc.’s antiviral remdesivir, and other antiretroviral drugs, initially developed for the treatment of HIV, have been identified as potentially useful. It is too early to say whether any of the medicines currently in clinical trials will turn out to be effective treatments for COVID-19.

Ultimately, scientists may end up in the same situation as they did in SARS, where the virus died out before a vaccine could be fully developed. Similarly, for MERS, vaccine candidates hadn’t yet progressed beyond early safety testing in people, but at least scientists have continued work on a MERS vaccine.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions about how the private sector and governments can timely develop vaccines before outbreaks occur. Clearly, the incentives provided by patent exclusive rights to private-sector investment in research and development need to be balanced against the global significance of this pandemic and the vast resources and infrastructure that governments can provide to control and eventually eliminate this health hazard.

The patent offices in the IP5 (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, European Patent Office, National Intellectual Property Administration of the People’s Republic of China, Japan Patent Office and Korean Intellectual Property Office)[22] must also focus on this technology area in order to encourage the building of the infrastructure necessary to encourage patents and innovation.

Gaby L. Longsworth, Ph.D., is a director and Robert Greene Sterne is a name director at Sterne Kessler Goldstein & Fox PLLC.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firm, its clients or Portfolio Media Inc., or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.

[1] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

[2] https://www.cdc.gov/sars/index.html.

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/index.html.

[4 ]https://www.the-scientist.com/image-of-the-day/image-of-the-day–67114.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] This data is current as of 3.2.20 reported by the World Health Organization.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Pasteur#Immunology_and_vaccination.

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glycoconjugate.

[13] https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/jonas-salk-and-albert-bruce-sabin.

[14] https://www.healthline.com/health/vaccinations.

[15] https://www.ip-watch.org/2014/06/10/access-to-vaccines-patents-growing-concerns-panellists-say/.

[17] https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/immunizations-policy-issues-overview.aspx.

[20] https://www.ip-watch.org/2014/06/10/access-to-vaccines-patents-growing-concerns-panellists-say/.

[21] https://cepi.net/.

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates